Ocean circulation collapse can happen within the next 30 years

A consequence of global warming that scientists have feared for years may be close to becoming a reality: the imbalance of ocean circulation.

A consequence of global warming that scientists have feared for years may be close to becoming a reality: the imbalance of ocean circulation. New studies point out that melting ice in Antarctica would cause a breakdown in the usual cycle of water across the globe, which could impact climate across the planet.

The predicted scenario, in research carried out by American and Australian researchers, indicates that — contrary to what was previously imagined — the collapse in ocean circulation should happen in the southern hemisphere and not in the North Atlantic. In addition, its term is much shorter than expected: instead of arriving only in the next century, the imbalance may come in the next 30 years.

At the same time, Swiss researchers have demonstrated that the circulation in the North Atlantic did not fail at the end of the last ice age — another theory that experts believed until then — showing that it is more stable than previously thought. The combination of these results indicates that the world’s attention, with regard to the balance of the oceans, must shift from hemisphere to hemisphere.

The Thermohaline Circulation

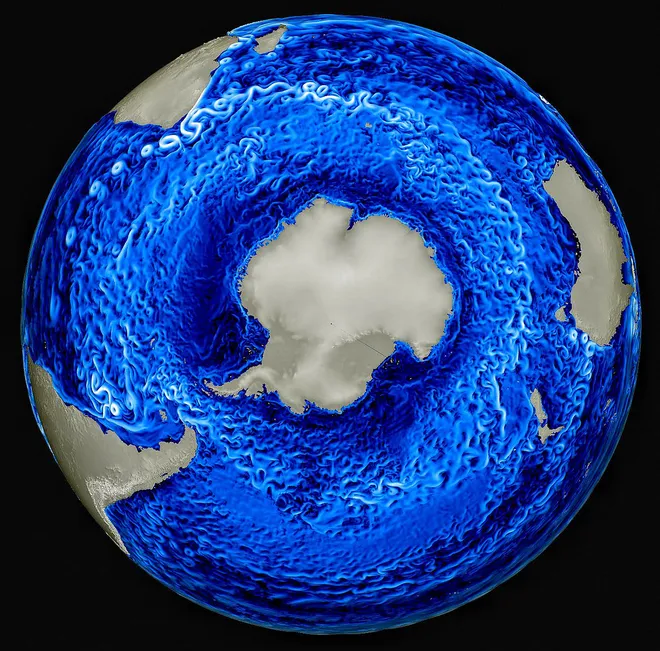

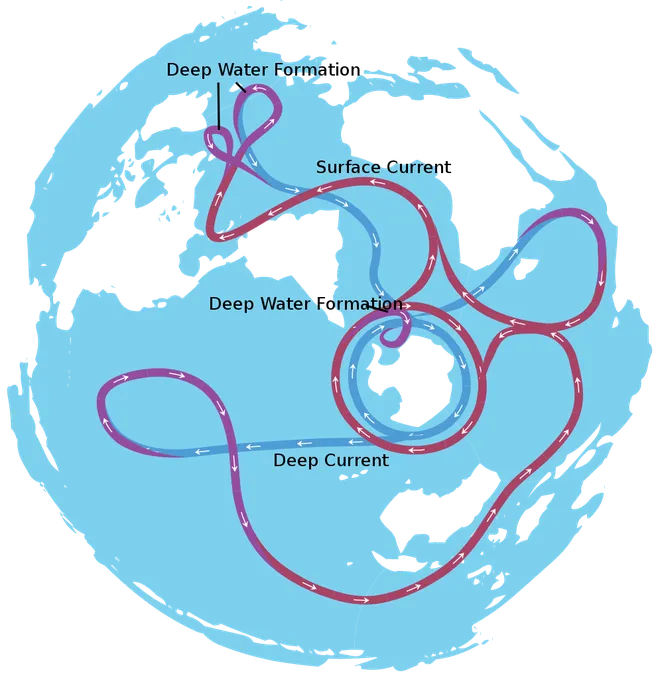

The great system of currents across the ocean — called the thermohaline circulation — follows a regular pattern, moving liquid through different depths and locations around the globe. This allows various inputs that water carries with it — nutrients, the carbon dioxide it absorbs and even the heat of the atmosphere — to be transported and dispersed.

Warmer surface water sinks into the ocean in just two places on the globe: in the North Atlantic, near Greenland, and in the southern hemisphere around all of Antarctica. In these places, the freezing of part of the water leaves behind the salt that it had dissolved. The excess of this material, in turn, makes the remaining liquid denser, allowing it to be able to sink into the ocean. Meanwhile, the water that was previously at the bottom is now able to rise and continue the cycle.

That’s 250 trillion tons of water sinking every year around Antarctica and a similar volume does the same in the North Atlantic. For thousands of years, the cycle remains the same, but with less ice forming annually, this dynamic is at risk.

Breaking the Current

With less sea ice forming and more glaciers melting, the water arriving through the thermohaline circulation is becoming less salty and less dense — hence, less able to sink. In the event of a collapse of oceanic circulation in the North Atlantic, one of the possible effects is the cooling of Europe, which would be deprived of the influence of warm water from the Gulf Stream.

On the other hand, the effects and dimensions of the collapse in the Southern Ocean have so far been less studied. New research indicates a 42% decline in water recirculation in this region by 2050: more than double the predicted rate for the Greenland region. Around the globe, this should be in a drier southern hemisphere and a wetter north. Furthermore, the dispersal of nutrients around the ocean will be completely compromised, affecting global marine life.

The worrying results for the Antarctic region do not, however, indicate that the thermohaline circulation in the North Atlantic is risk-free, only that the worst situation must be on the opposite side of the globe. Experts also consider it necessary for climate models to incorporate new discoveries and for their results to help global leaders make better decisions about environmental issues.

Via: Yale Environment